I only drink Champagne on two occasions, when I am in love and when I’m not.

Champagne is one of the most luxurious wines in the world. It’s high price tag and French pedigree are part of the reason but, equally so is its enduring association with some of the most glamorous people in history. Iconic fashion designer Coco Chanel, King Louis XV’s paramour, Madame de Pompadour, and legendary actress Marilyn Monroe were all huge fans who were known to passionately extoll the gloriousness of this sparkling elixir.

But Champagne is fascinating from a technical perspective as well.

From the intricate way it’s made to the rich history of the region it comes from, Champagne is truly the unicorn of the wine world and this essential Champagne 101 guide will demystify this vinous treasure for you and reveal all the basic fundamental information you need to know. And if you just so happen to be on a quest to broaden your vinous horizons and increase your knowledge base in the world of wine, be sure check out my White Wine 101 and Red Wine 101 posts as well.

But first things first.

In ANY discussion about Champagne it's important to note that while ALL Champagne is sparkling wine, NOT ALL sparkling wine is Champagne. Only sparkling wine from the actual Champagne region of France can be called Champagne. So even if a sparkling wine is made using the same grapes and the same method as Champagne but it comes from outside the geographic region, by law it cannot be called Champagne.

And if you try to call it that, they will sue you.

Yes, the Champenois are litigious…but for good reason. In the early days of California wine country, the habit of featuring the term “California Champagne” on bottles of sparkling wine became pretty widespread. Eventually, the Comité Interprofessionnel du vin de Champagne (aka the CIVC), the governing body of the Champagne region, took umbrage at this vinous appropriation and took action. Well, sort of.

While all Champagne is sparkling wine, not all sparkling wine is Champagne.

The “Treaty of Versailles” was drafted in 1919 following WWI and it addressed this issue among many others, however, the treaty was never ratified by the United States which was in the midst of Prohibition at the time, so it hardly seemed relevant. Once Prohibition ended in 1933, however, U.S. wine producers were still free to continue to legally use the term “Champagne” on their bottles, much to the chagrin of the Champenois.

Thankfully, over the years many New World winemakers began using the term “sparkling wine” instead of Champagne on their sparkling wine bottles and in 2006 the U.S. and the European Union finally signed a wine trade agreement. In it, the U.S. agreed to no longer allow any new uses of certain place names on wine bottles, however, anyone who already had an approved label such as Cook’s, Korbel, André and Miller High Life were grandfathered in and are still allowed to use the Champagne name to this day.

More recently, companies outside the wine world like Apple, Perrier and Yves Saint Laurent have also felt the legal wrath of the CIVC when they tried to use the Champagne name in association with their products. This CIVC’s vigilance has paid off, however, and helped to preserve the history and integrity of the Champagne name.

“So what’s the big deal?” you might ask. “All these decades of strife over a name?”

I’m SO glad you asked!

Ruinart’s depiction of how Champagne’s legendary chalk caves were dug.

You see, Old World wine regions like Champagne are ALL about the concept of terroir, a French term that describes the way a wine reflects the place it comes from. Perhaps more accurately, terroir refers to the intersection of grape variety, climate and soil type and how these components come together to produce a wine that can’t be duplicated anywhere else in the world.

Old World wine regions have had centuries to perfect their knowledge of their land and they now definitively know which regions grow which grapes best. That’s why nobody in Burgundy is growing Cabernet Sauvignon and nobody in Champagne is growing Syrah. Because of this, they identify their wines by region rather than by grape variety like we do in the US. The same concept applies to food products like Prosciutto di Parma and Comté cheese which come from specific places in their respective countries.

Alternatively, here in the U.S., we’ve only been making wine for about 200+ years and we’re still experimenting with growing different grapes in different regions. In Napa Valley alone, one of our country’s oldest wine regions, you’ll find vineyards dedicated to numerous grapes including Sauvignon Blanc, Zinfandel, Cabernet Sauvignon and Refosco. So we label our wines by grape variety rather than location which is why deciphering Old World wines can be somewhat of a challenge…but one definitely worth accepting!

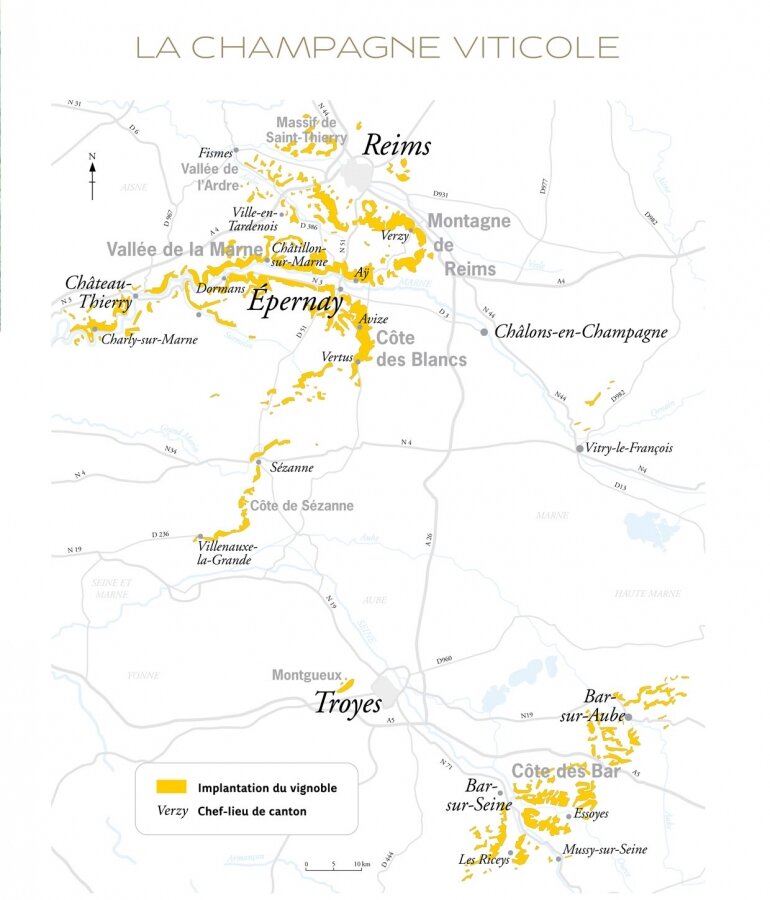

The Champagne production zone (AOC vineyard area) was defined by a law passed in 1927 and encompasses roughly 34,300 hectares of vineyards. It lies approximately 100 miles northeast of Paris, spreading across 319 villages (‘crus’) in five departments: the Marne (66% of plantings), Aube (23%), Aisne (10%) and Haute-Marne + Seine-et-Marne.

A primary distinguishing feature of the Champagne region is its sheer geographic location, the grapevines are planted at the northernmost limits of their cold tolerance. Average annual temperature in Reims and Epernay (latitudes 49°5 and 49° North) is just 50°F and vines, like all plants, require minimal weather conditions to survive and in the Northern Hemisphere, they rarely thrive beyond latitudes 50° North and 30° South.

The region’s second major distinguishing feature is its dual climate, which is predominantly oceanic but with continental tendencies. Champagne also receives barely 1,650 average annual hours of sunshine compared with 2,069 in Bordeaux and 1,910 in Burgundy. The growth rate is accordingly limited, giving the grapes the freshness and crispness that Champagne requires.

There are also four main growing areas (see map below):

The Montagne de Reims: Its soils are chalk-based, with striations of loam, lignite, clay, sand, silt, and marl. It contains nine Grands Cru villages and Pinot Noir is the main grape cultivated here.

The Vallée de la Marne: This sub-region is located on the riverbanks of the Marne and its soils are more variable than in other Champagne sub-region. It contains only two Grands Cru villages: Ay and Tours-sur-Marne and Pinot Meunier is the main grape variety planted here.

The Côte des Blancs: This sub-region owes its name to the color of the grape that is planted there: 95% Chardonnay. Champagnes produced in this area often include the term "blanc de blancs" and it is the source of Chardonnay for many vintage Champagnes and prestige cuvées from the large Champagne houses. Only four villages are located on the actual Côtes des Blancs slope, namely Avize, Cramant, Le Mesnil-sur-Oger and Oger which are known for producing wines with light, delicate aromas and finesse and elegance.

The Côte des Bar: This is the only major sub-region in the Aube, located southeast of the town of Troyes. Pinot Noir is the predominant grape grown here although small amounts of Chardonnay and, to a lesser extent, Pinot Meunier can be found here as well. Other approved grape varieties that are seldom used can also be found here including Pinot Blanc, Arbane and Petit Meslier.

Together these regions encompass nearly 280,000 plots of vines, each measuring roughly 12 acres (100 square metres). Seventeen villages have a traditional entitlement to Grand Cru ranking and 42 to Premier Cru ranking.

Unlike the vintage dated wines we’re used to seeing on store shelves that represent the majority of wines produced, Champagne is first and foremost about the art of blending.

With few exceptions, most Champagnes on the market are a blend of grapes, vintages and vineyards. With respect to the most common type of Champage produced, non-vintage Brut, these components are brought together by the winemaker with the express intention of creating consistency from year to year. They do this using the three main approved grapes in Champagne that each bring a little something different to the wine:

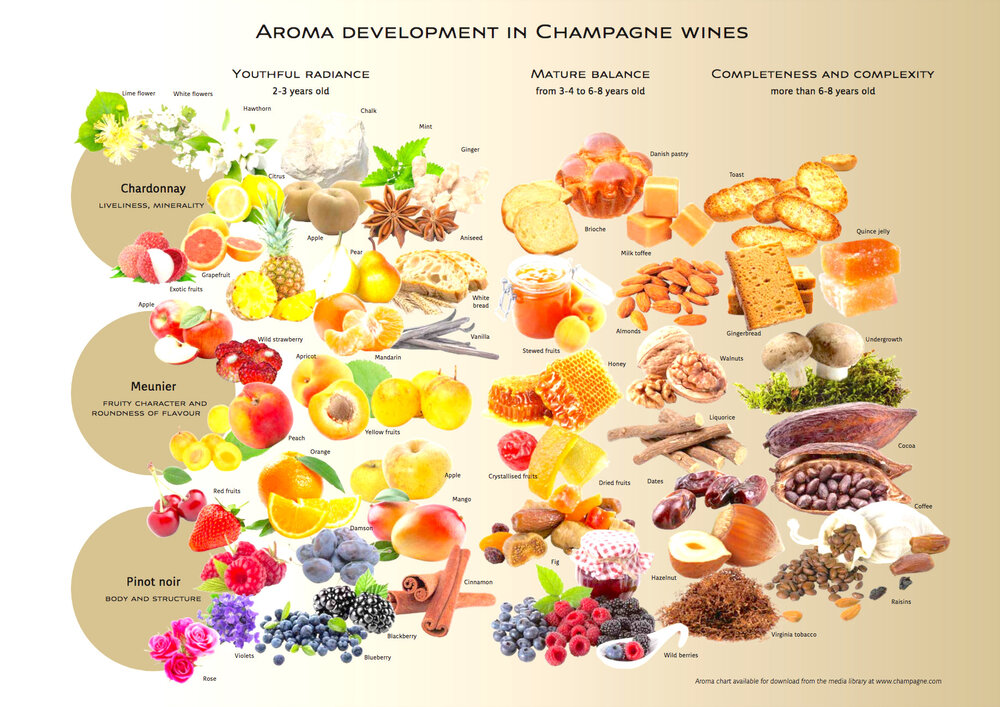

CHARDONNAY: The only white grape of the Champagne trinity, Chardonnay contributes elegance and acidity to the finished wine, allowing it to age with grace and finesse. Chardonnay accounts for 30% of the region’s plantings and does particularly well in the Côte des Blancs where is yields delicately fragrant wines with characteristic notes of flowers, citrus and minerals. It is the slowest to mature of the three Champagne varietals and also the longest-lived.

PINOT NOIR: Accounting for 38% of plantings, Pinot Noir grows particularly well in the cool, chalky soils of the Montagne de Reims and the Côte des Bar. Pinot Noir adds backbone, body and heft to the blend, producing wines with distinctive aromas of red berries and good structure that can also age particularly well.

PINOT MEUNIER: The least well-known of the three grapes, Pinot Meunier accounts for 32% of plantings in the region and shows better cold-weather resistance than Pinot Noir, which is notoriously difficult to grow. Meunier is well suited to the soils of the Marne Valley and adds roundness to the blend, producing supple, fruity wines that tend to age more quickly than wines made with the other two varieties. Therefore it is most useful in non-vintage Champagnes intended for near-term drinking.

All Sparkling Wine undergoes a secondary fermentation to get its bubbles, and it’s WHERE Champagne undergoes its secondary fermentation that makes it so uniquely special!

By law (Old World wine regions have lots of laws regarding winemaking!), Champagne must undergo its secondary fermentation in the bottle it is later sold in. This is the main tenet of the Méthode Traditionelle (aka Traditional Method and Méthode Champenoise) which is the only method that can be used to produce Champagne. This is a much more time- and labor-intensive method of making sparkling wine compared to the Charmat Method that’s used to make Prosecco in which the secondary fermentation takes place in a tank.

Once primary fermentation has occurred and the base wines have been blended and bottled, a combination of still Champagne, beet sugar and yeast (aka “liqueur de tirage”) is added to each individual bottle to kick start the magical, bubble-inducing secondary fermentation. During this critical transformative process, the yeast consumes the sugar, thereby creating alcohol and carbon dioxide in the bottle. As the yeast cells complete their job, they eventually die and fall to the bottom of the bottle where they are referred to as “the lees.”

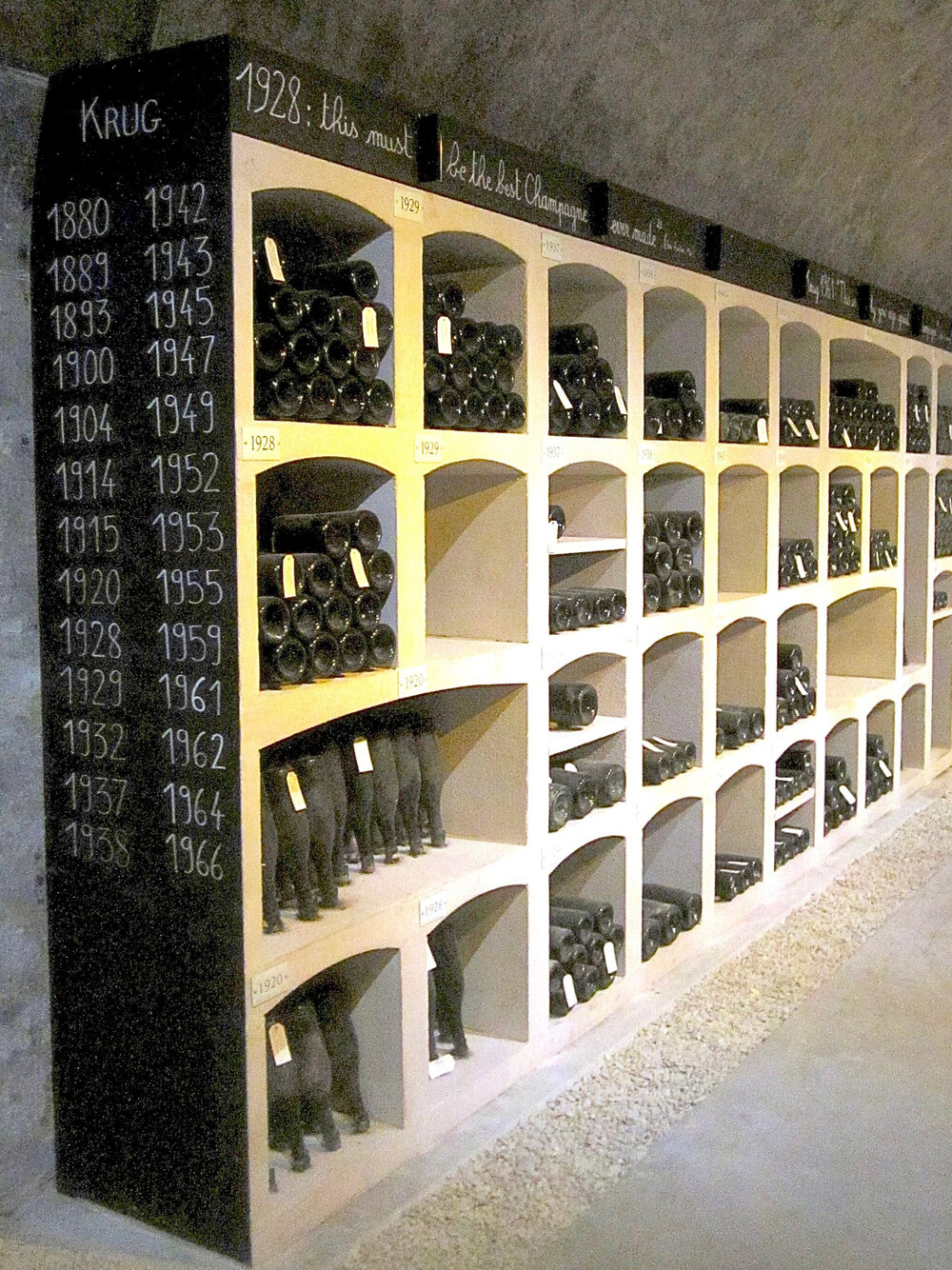

The lees impart a very desirable, biscuity, yeasty note that is a sensory hallmark of Champagne and other wines produced using the Méthode Traditionelle. The longer the wine remains in contact with the lees or dead yeast cells, the more pronounced this quality will be. By law, all Champagne must spend at least 15 months in the bottle before release, of which 12 months maturation on lees is required for non-vintage cuvées and three years minimum for vintage cuvées.

In practice however, most of the well-known Champagne houses cellar their wines for much longer, usually 2-3 years for non-vintage wines and 4-10 years for vintage Champagne. It’s important to note these wines spend this time maturing in the legendary chalk caves that lie deep beneath the city of Reims (see video below to see the cellars at Krug Champagne).

Towards the end of their long resting period, the Champagne bottles must be moved and rotated in order to collect and remove the sediment which is comprised largely of the aforementioned lees or dead yeast cells. This is accomplished through the process of riddling (aka “reumage”) in which the bottles are placed in A-shaped riddling racks, also known as "pupitres."

Initially, the bottles are placed in the racks horizontally, parallel to the floor and gradually, over time, they rotated and inverted either manually or mechanically by gyropalette. This motion causes the sediment to collect in the neck of the bottle where it is ultimately disgorged. Prestige cuvées are usually “riddled” manually which takes about 2-3 months while less expensive sparklers are done mechanically which takes approximately one week.

Once the bottles are completely inverted or “sur pointe” they are ready for disgorgement (aka dégorgement). During this time and labor-intensive process the neck of the bottle containing the sediment is plunged into a freezing solution, the temporary crown cap is then removed and the pressure inside the bottle causes the freezing plug to shoot out (watch video here), while spilling as little actual wine as possible.

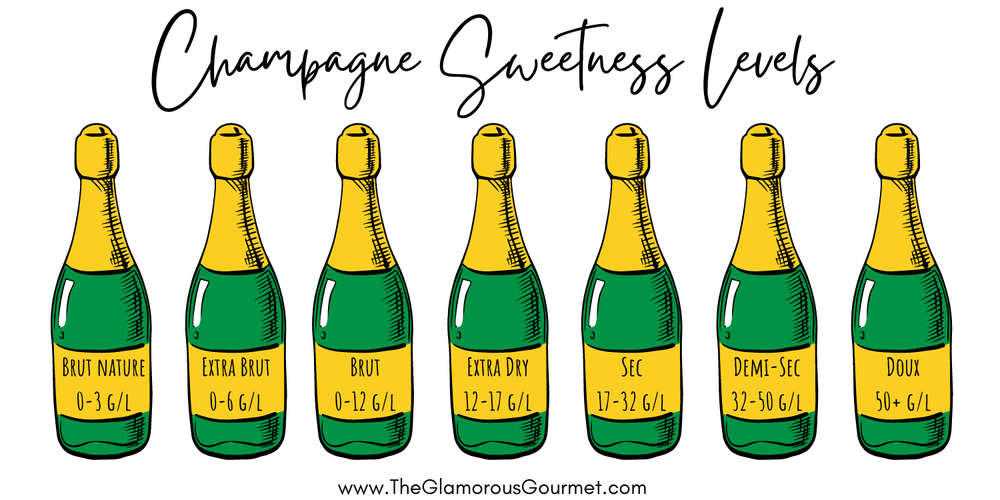

Before the bottle is sealed with a cork, there’s one more very important step: dosage. In order to replace any wine lost during disgorgement, the bottle is topped off with liqueur d’expédition, a mixture of wine and sugar that determines the sweetness level of the finished wine as well. The seven levels of sweetness are determined by the grams per liter of sugar (g/l) added during dosage (see graphic) and by law, that sweetness level must be included on the bottle’s label.

“Brut” is the most common classification you’ll encounter on store shelves followed by “Demi-Sec” and, more recently, “Brut Nature” which has become more popular in recent years due to its low level of sugar. It’s important to note, however, that sugar is added to Champagne mostly in order to balance its high acidity level. For instance, while Brut Champagne can contain up to 12 grams of sugar, it is intended to be perceived on your palate as dry. Due to the Champagne region’s cool climate, the grapes struggle to attain ripeness resulting in wines characterized by high acidity levels and the addition of sugar helps to create a more balanced and enjoyable sensory experience. It’s really not until you get to the Sec/Demi-Sec levels that the wines start to have a noticeable sweetness.

The Méthode Traditionelle concludes with sealing the bottle with a cork. The cork is squeezed into the bottle, covered with a protective foil capsule and then secured with a wire cage (aka muselet) to create an airtight seal. Champagne bottles are thicker than normal wine bottles because they must be able to accommodate the build up of pressure caused by the secondary fermentation. When you’re down in the chalk caves, every so often you’ll hear a “pop” when one of the sleeping bottles breaks due to a flaw in the glass.

Once corked, the bottles continue to age in the cellar until the winemaker deems them ready for release onto the consumer market. The natural, porous cork allows for micro-oxygenation to occur, and for that reason Vintage and Tête de cuvée Champagnes are excellent candidates for aging.

NON-VINTAGE BRUT: The most common type of Champagne, non-vintage Brut is a blend of vintages, grape varieties, vineyards and consists of 85% of Champagne made. It is comprised primarily of the current vintage’s wine with between 15-40% base wine from previous vintages added to create a similar tasting wine from year to year. While we mostly think of wines as a reflection of the vintage they’re from, non-vintage Brut is the exception to this rule. Consistency is the winemaker’s goal because this wine represents the “house style” and it is unique to each brand of Champagne.

For instance, Taittinger is known for its extensive Chardonnay holdings so its non-vintage “Brut la Francaise” is predominantly made of up Chardonnay with smaller percentages of Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier. On the other hand, Bollinger favors the Pinot Noir grape so their “Special Cuvée” is comprised predominantly of Pinot Noir with small amounts of Chardonnay and Pinot Meunier as well.

VINTAGE: Conversely, Vintage Champagne is blended from the wines of a single ‘millésime’: a single outstanding year that the individual producer chooses to declare a vintage. These wines are only created in those years that are deemed outstanding by a particular house and thus, are meant to reflect all the nuance of the given year. Unlike non-vintage wines, only grapes harvested in the year featured on the label may be included in vintage-dated wines.

PRESTIGE OR TETE DE CUVÉE: At the opposite end of the spectrum from a Champagne house’s non-vintage Brut is their most special offering aka their Prestige Cuvée or Tête de Cuvée. This Champagne is usually comprised of the best of the best of everything that house has to offer and they are proprietary and unique to each house. And they can vary is styles and types too! Some are vintage some are non-vintage. Some are Blanc de Blancs and some are Rosé. It just depends on what the Champagne house wants to do.

Examples of well-known Prestige Cuvées include Louis Roederer’s Cristal, Moët & Chandon's Dom Pérignon, Taittinger’s Comtes de Champagne, Perrier Jouët's La Belle Époque and Veuve Clicquot’s La Grand Dame.

BLANC DE BLANCS: This French term translates to “white from whites” and refers to Champagnes made exclusively from Chardonnay grapes. These wines are generally lighter-bodied with a racy acidity that truly highlight the immense potential of the Chardonnay grape.

BLANC DE NOIRS: This French term translates to “white from blacks” and refers to a white wine (Champagne) made exclusively from black grapes which in Champagne are Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier. As long as you separate the juice from the skins, you can make a white wine from black grapes as is the case in the Champagne region. These wines are fuller-bodied with a richer mouthfeel, reflecting the characteristics of the grapes it’s made from.

ROSÉ: This name of this style refers to the beautiful pink color of the Champagne that gets its color one of two ways: (1) saignée or (2) blending in still red wine. The saignée method requires the wine to get its color by macerating the juice with the actual grape skins for a period of time. This method produces a Champagne that more closely resembles a red wine with more tannins which are extracted from the colored skins. While forbidden in making still rosé wine, blending still red wine into Champagne to create a Rosé gets a thumbs up from the CIVC! This method also gives the winemaker more control over the process but both methods produce truly delicious, bone dry (NOT sweet!) Rosé Champagne.

Which glassware you use when serving and enjoying Champagne will depend on the type and style of wine you’re serving as well as the occasion.

If you're popping a non-vintage Brut Champagne to celebrate a festive occasion or enjoy with brunch, by all means break out the flutes! Tulip-shaped, crystal flutes are ideal (avoid those thick, rolled-rim glasses at all costs!) because they allow the aromas of the Champagne to focus in the headspace of the glass where they can be readily enjoyed while still feeling celebratory, glamorous and fun.

But, if you're enjoying a pricier bottle like a Vintage or Prestige Cuvée Champagne, especially if it’s been aged, I highly recommend breaking out your White Burgundy or white wine glasses. The larger bowl and shape of these glasses is perfect for appreciating the complex aromas and flavors of these wines that have developed over time.

You also want to serve special or aged Champagnes slightly warmer than the recommended 45 degrees for most sparkling wines. As these graceful, elegant wines warm up (i.e. 50 degrees), their aromas and flavors are more readily able to be savored and enjoyed.

I hope you my Champagne Wine 101 helpful and that it inspired your understanding of this truly delightful wine. If you have any additional questions about anything you’ve read, please let me know in the comments section below. And when you’ve sufficiently soaked up all of this information, please proceed to the next two 101 installments: White Wine 101 and Red Wine 101.

Stephanie Miskew

Author